Image: Chester Bullock on Shotzr images

Introduction

It is interesting to reflect on how pricing has developed over time. In early civilization, people would trade, barter, and auction items for sale in person and information asymmetry was pronounced (no search engines to find comparative products or reviews). Pricing was always customized through a process of negotiation. Today, most companies offer standard pricing on their websites (except for enterprise sales where you will commonly see the “contact us for pricing” option) and consumers have significantly greater access to transparent information on products and competitors.

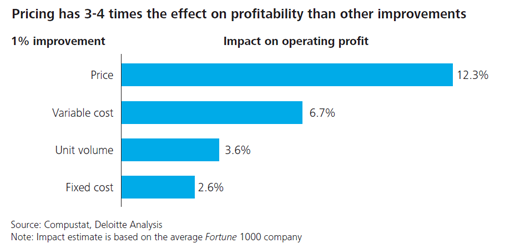

Pricing is a very effective value driver. A Deloitte study found that pricing is the most impactful lever on profitability – a 1% improvement in a company’s average price has an approx. 2-4x bigger impact on overall profitability than a 1% increase in sales volume or a 1% reduction in fixed or variable costs.

Source: Wall Street Journal/Deloitte

This is not to suggest that everyone should just go and raise raise prices. Pricing is hard to get right, especially for early stage technology companies with limited past purchasing behavior, only the earliest signals of market feedback, and immense pressure to drive early customer adoption.

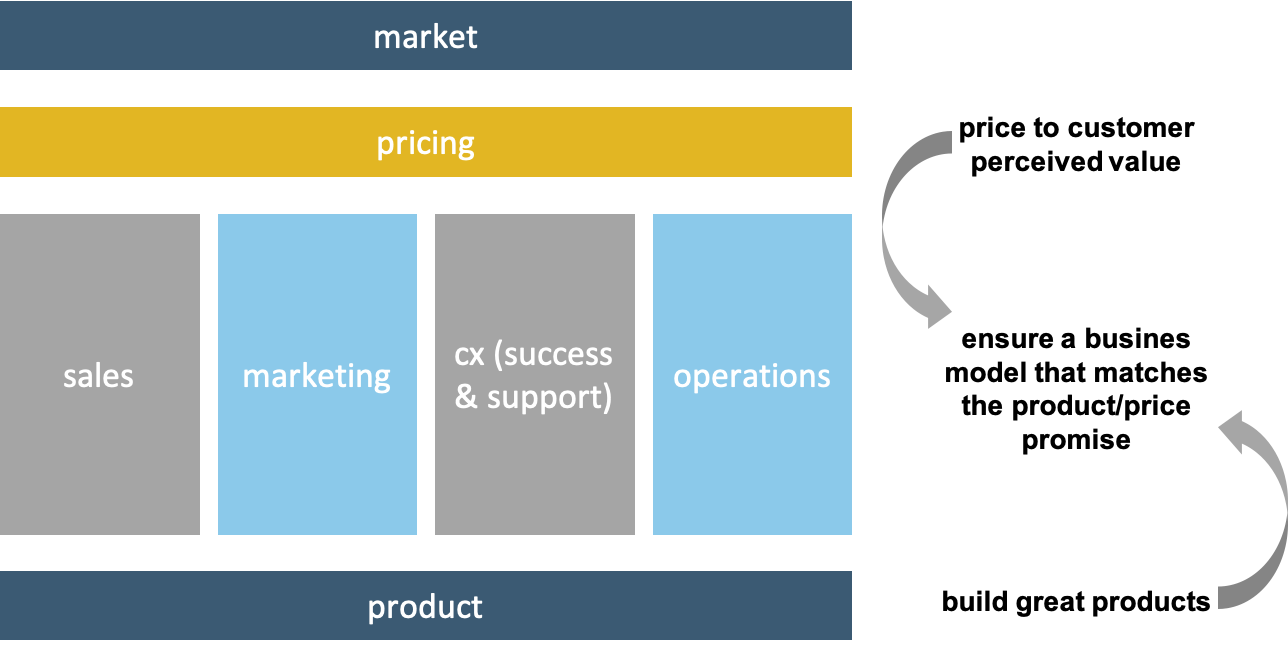

Pricing is also contextual, and must fit like a puzzle piece into your overall schema of market, product, and business model. People always talk about product-market fit, but I believe product-market-business model fit is a much better definition of the core elements that must to come to together to to set the stage for growth. It is pointless having an amazing product that is priced perfectly for customers at $1 / year and ready to scale aggressively in a large market… if your business model to successfully deliver on the product will cost $2 / year per customer. All moving parts must fit.

Source: the product-market-business model fit model

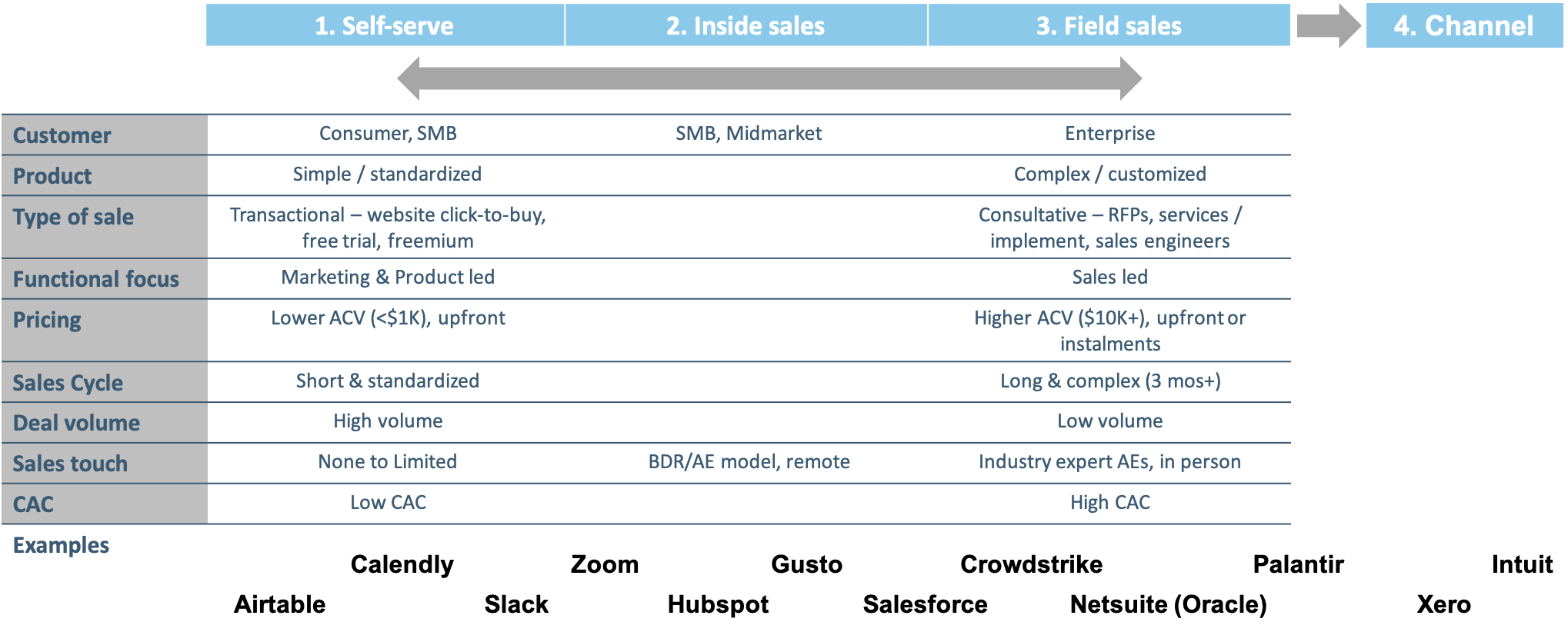

The below graphic shows how the “product-market-business model fit” equation can express itself through the dominant go to market business models that orientate around self-serve, inside sales, field sales, and channel sales.

Source: the 4 go-to-market business models

Source: the 4 go-to-market business models

Setting yourself up early with the right methodologies and processes for thinking about pricing is a good idea. Common pricing pitfalls made by early stage startups are (a good discussion on this topic):

- Basing prices off of competitors, research, and existing market conditions instead of from talking to customers and ascertaining actual customer value

- Setting prices in stone and not continually reviewing and adjusting them over time

- Setting prices too low to attract early customers and never raising them over time (it can be easier to drop prices over time than to raise them later)

- Offering features for free (or lumping them in with an existing package) even when it is clear customers will pay extra for them

- Building pricing structures that are too complicated to understand, with the objective of trying to cater to a multitude of individual use cases

It is also important to note that within startups, there are often conflicting viewpoints to navigate – sales might want to keep pricing lower to maintain sales momentum, while finance might be pushing for higher pricing without necessarily having full visibility into the coalface.

General Approaches to Pricing

Fundamentally, there are five core pricing approaches that companies incorporate into their pricing strategy, some more common than others:

1. Value based pricing

Setting a price based on how much the value the customer believes or perceives your product is delivering. This is the most common and accepted approach to thinking about pricing, and you may have heard advice along the lines of “compete on quality, not price” or to “work backwards from the customer’s willingness to pay”. This is obviously the standard approach of enterprise B2B companies, who often craft custom pricing for customers based on the ways in which the customer plans to use the product – often the approach if to try to ascertain what factor is the key driver of customer perceived value (amount of data, seats, features, modules, etc) and price the product based on that.

2. Cost plus pricing

Calculating the costs for building your product or delivering your service and then marking that up for a profit margin. This has been a common approach in many large infrastructure industries such as construction and aerospace as well as professional services businesses such as consulting, where the materials and labor involved are a large part of the cost and there is a lot of customization involved. Another newer and slightly nuanced take on cost plus pricing might be the dynamic pricing employed by Lyft and Uber – “surge pricing” is effectively just adjusting the price the consumer must pay as a function of the cost of the service (the higher cost of getting the driver in peak periods) plus the standard mark up

3. Competitive pricing

Charging a price based on what your competitors are charging and how your product compares relatively. This is a common pricing model in “commodity markets” where there is limited product differentiation – you might notice how when your local gas station drops fuel prices, the one down the road soon follows suit. This can also often be the pricing strategy for a company entering a market where there are established incumbents who charge high prices and the new entrant’s strategy is to compete predominantly on cost efficiencies. Spacex, for example, charged into the aerospace industry with the promise of building rockets (through improved production methods) for the government at a cost of $80-90 million versus the United Launch Alliance’s average cost of $400 million. “Price bundling” is a common way to build pricing leverage over competitors, offering larger discounts for purchasing product bundles

4. Price skimming

Setting a high price to land your first customers, and then iteratively lowering it as the market evolves, competition enters, you reduce production costs through scale, and/or you satisfy the highest value customers and need to extend to more price-sensitive segments. Price skimming might make sense where there are high production costs that need to be recovered before scale is hit, there are enough buyers willing to buy the product at the higher price, and/or the higher price might be a market signal for quality. Oftentimes, luxury brands might enter a market like this, and then later set up a separate sub-brand to extend themselves into other parts of the market with greater distribution (think Ralph Lauren and Polo). Peloton and Tesla are also good examples too – they both set high prices for their early products, gained premium brand positioning and secured market share with high net worth households. Now they have created lower priced products to extend further into the market.

5. Penetration pricing

Setting a low price to enter a competitive (or blue ocean) market and gain market share and then raising it later once you have more market dominance. This has been a common approach in recent years particularly in markets considered “land grabs” or “winner take all”, where rapid customer adoption has been deemed critical to success. Fierce penetration pricing and discounting has defined many recent consumer marketplaces, such Uber / Lyft, Doordash / GrubHub / Postmates, Rover / DogVacay, etc.

The right approach for you depends ultimately on the nature of your industry and business, what your objectives are, and who your customers are. For companies in the early days, your key objective might be:

- Maximizing revenue (which might guide you to value based pricing)

- Gaining rapid market share (which might guide you to penetration pricing)

- Securing your first publicly reference-able customers (which might guide you to competitive pricing and optimizing on value delivery and sacrificing revenue for the short term to ensure early customer success)

- Landing key customers to later expand (which might lead you to some initial price discounting with a roadmap to growing)

That said, value based pricing is the most commonly accepted approach and is, in general, a logical framework for most companies.

“Value Based Pricing”

The objective of value based pricing is to ascertain as best you can the customer’s perceived value from your product and “willingness to pay”, and then use that to inform your pricing plan (as well as product roadmap, with the view to building features to grow that value).

Value-based pricing is a good approach as it orientates your company around the customer and toward building feature differentiation that grows value.

Remember that the key here is setting your pricing based on customer perceived value, not actual value. Funnily enough, pricing (in a virtuous, reinforcing cycle) actually ends up being a major input into customer perceived value – when you walk into a liquor store, you automatically think the $30 bottle of wine is more valuable than the $10 bottle.

Some of the best companies I see not only price their product closely to customers’ willingness to pay, but take it a step further and peg their pricing model to a key value driver, such that customer ROI is baked into the pricing model itself.

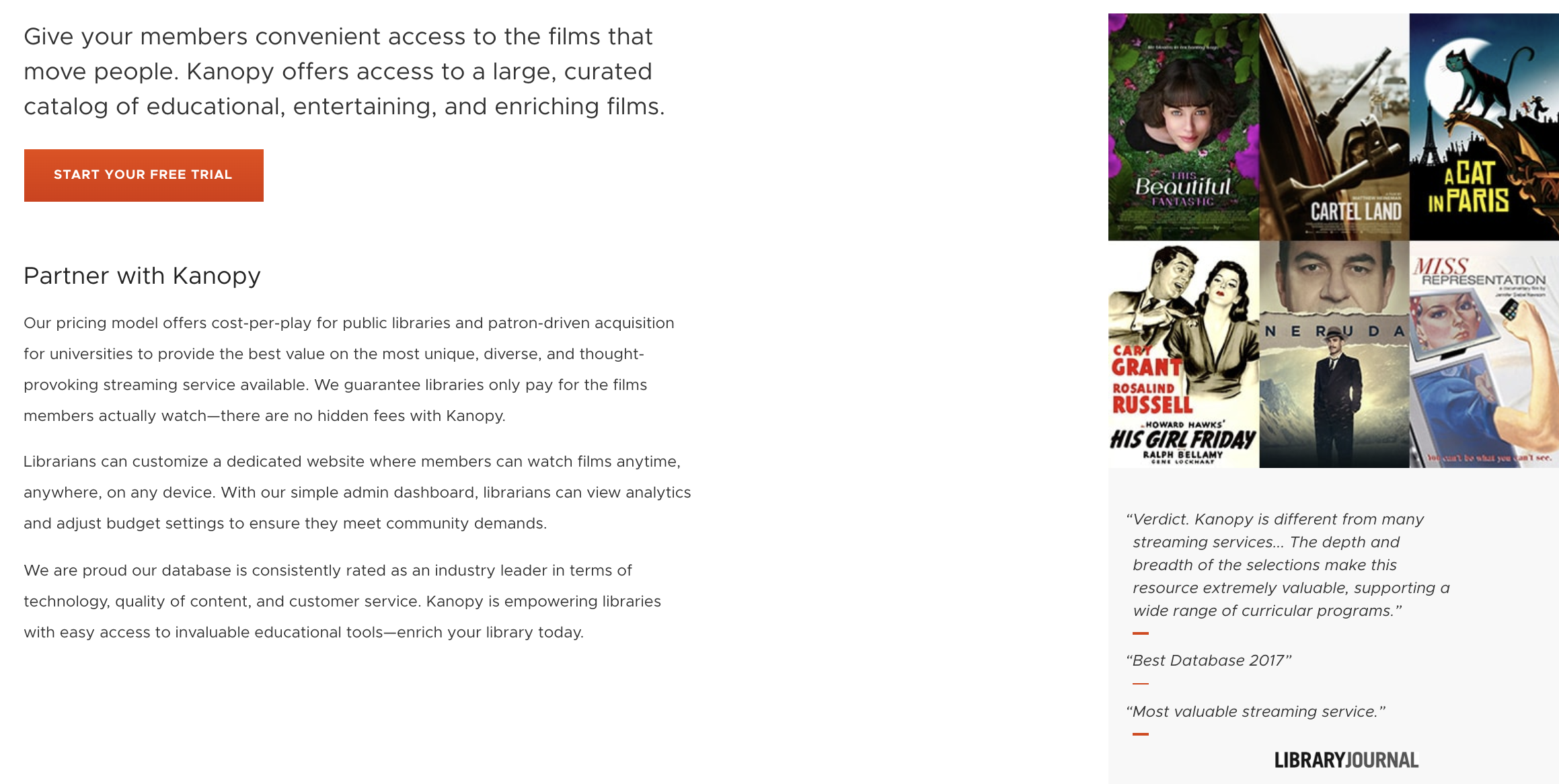

At my last company, Kanopy, we entered a market where existing incumbents sold large content packages to universities and colleges for a large fixed upfront price, meaning customers had to build the business case upfront to justify the purchase (will this be used? how much will it be used? is that a better purchase than the other options we have?). We flipped the pricing model on its head to a cost-per-use model with no upfront cost and monthly billing – which meant that 1) customers didn’t need to craft the business case upfront (“we will only charge you if you get value and you know exactly what your ROI will be”) and 2) our entire company was orientated around delivering end use value, because if we didn’t, we didn’t get paid.

Source: Kanopy

So how to execute on “value based pricing” –

Step 1: Do Your Customer Discovery

Beyond all of the other questions you might do in talking to early customers for your idea validation, some good pricing discovery questions may include –

- What is the last software solution you bought? Tell me about that evaluation process.

- If I told you that I have a solution for [insert pain point], would you be interested? Why?

- What do you think is an acceptable price for a product that solves this problem?

- What is an expensive price?

- What is a really expensive price?

- What is your budget for a solution in [insert your product category, such as BI/analytics, security, collaboration tools etc]?

In working through this process, you need to remember that actions speak louder than words and often people might say one thing but do another. The price a customer says they will pay is never as powerful as the price they actually do pay.

Step 2: Test Pricing on Early Customers

- Build hypotheses around what you think you can charge certain customers for your product then test it with some early customers (say 5-10 to get a meaningful sample)

- Deliver the pricing over the phone / in person if you can (versus an email), so you can gauge the reactions. If they’re adverse to the price, ask open-ended questions that expose the root causes of their anxiety, and then re-evaluate

- Make sure you have done the job of communicating the product value before you discuss pricing

What you want to learn from these meetings and early deals:

- Your upper bound – the highest price range that the market will allow you to charge for your current product. There is a tendency to want to close deals at any cost in the early days, and you might feel uncomfortable pushing for a high price but remember the objective here is to learn how far they will go, if you have done a good job at communicating the value the customer most likely won’t balk, and you can always scale back on the pricing offered at first through tactics such as “let me see if I can chat to my colleague about a discount” or “if we can do a 2 year deal, I could probably reduce that” or “we are an early stage start-up still figuring out of our optimal pricing – what can we do on price to make this work for you?”

- Your anchor – the thing that the customer will typically compare your product against as the alternative or replacement option. Ideally you can set your anchor to something the customer understands – e.g. “our software replaces the need for a HR administrator, who typically makes around $75k per year”. Ideally your anchor is something of high enough value to justify the pricing you propose

- Your messaging – the key words and features that signal the value of your product and that customers want to hear. For example, Weebly initially marketed itself as being “free and easy”, but that insulated in the market the idea of being “cheap and low value”. Over time, Weebly adapted their messaging to be “create a site as unique as you are”, which better aligned to the perceived customer value proposition (even if being free was a real driver)

- Your ideal customers – the key profile factors (size, budget, etc) and trigger elements (specific events, timing, etc) that make for an ideal customer

Step 3: Build Customer Personas

Customer personas are representations you use to profile segments of your customer base. They help you to understand your customers and better tailor your products and pricing to them. Personas can be based on qualitative features (job titles, interests) or quantitative measures (customer acquisition cost, price sensitivity, size).

You want to be specific with your personas – for example instead of saying we sell to “software developers”, you might say we sell to “developers who use Python and have teams of 10-50 people”. This is not to say you can’t sell to people outside of those highly specific personas – this is more just guiding the core people for whom you will design your key messaging, go-to-market and pricing.

Some of the key factors you want to understand on your personas:

- Who are they? Define their background, demographics and presumed personality

- What are their motivations? What are their goals and challenges, and how can your product help them reach their goals and overcome challenges?

- Why wouldn’t they want to use your product? What issues would they have with it?

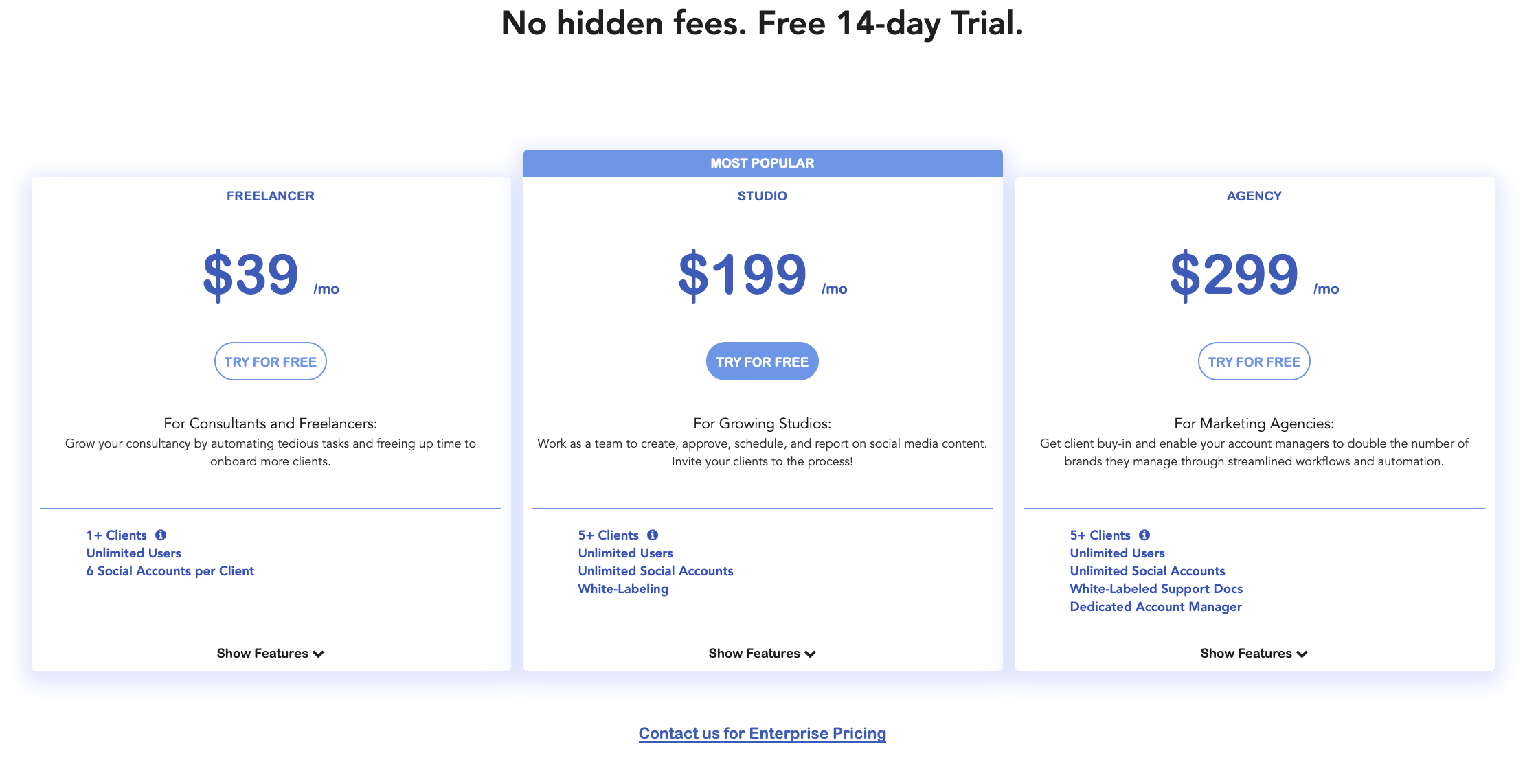

You may keep these personas more for internal use (to guide how you think about your marketing and product etc) or you may even orientate your packages and pricing directly around them. An example of this is Cloud Campaign, who has structured its pricing packages around freelancers, studios, agencies, and enterprise in its market.

Source: Cloud Campaign

Source: Cloud Campaign

Key Pricing Tips

1) Recurring revenue is premium

Whether your product is a technology solution, a service or project-based, the first step to your pricing is determining the right revenue model. The two primary revenue models are recurring and transactional.

Recurring revenue is where a business has continuous, repeatable revenue based on an ongoing service. Much pricing we see today is recurring, such as Netflix, Spotify, Amazon Prime, etc. For consumer platforms, this revenue is often called subscription revenue. For B2B companies, it is often called “SaaS” or Software as a Service revenue (almost all B2B startups today shoot for SaaS revenue). More interesting recently has been the invention of the “RaaS” model for large capital goods businesses – rather than sell a large capital item for a one time fee, rent it on an ongoing basis with a maintenance and servicing package included.

Transactional revenue, on the other hand, involves a one time payment for a good or service through a transactional purchasing process. Transactional pricing makes more sense when customers make large but infrequent purchases or the product is completely different for each purchase (e.g. at Whole Foods, I might buy toothpaste today but avocados tomorrow). Other common examples include Airbnb (where you transact each time to make a booking for a property), Sephora (where you add things to your cart before purchase), or Ticketmaster (where you buy tickets for individual events).

Recurring revenue is the model most prized pricing model by investors. “Companies with SaaS software models averaged a 6x revenue multiple, twice as high as the 3x revenue multiple that perpetual software companies average”. On April 23, 2012, Adobe moved from a non recurring revenue-based product model to a recurring revenue-based subscription model when it announced Adobe Creative Cloud. This change resulted in a 35% decrease in revenue the following year. However, according to Harvard Business Review, “in April 2016 Adobe’s stock price had nearly tripled from its value four years earlier.”

Source: Adobe Stock Price, Bloomberg

Source: Adobe Stock Price, Bloomberg

Why is this the case? Recurring revenue models are attractive because they have more predictable revenue streams and customer behaviors (such as churn), are less prone to seasonal fluctuations and instability, and typically require lower ongoing costs through better expense management and not having to continually engage customers to re-buy.

Many of the leading companies in verticals today have managed to turn traditionally transactional businesses into recurring, even in markets that might have seemed ill suited to recurring beforehand. For example – I used to buy Microsoft Office as a one time software package for my computer and now am nudged toward an annual subscription which follows me to all my devices. I once bought music on iTunes, and now pay $9.99 per month to Spotify. The purchasing of ski tickets was typically transactional for a single day or week and bought at resorts, until Vail Resorts came along and invented the yearly Epic Pass. Peloton turned the purchasing of a bike into an added content subscription package. Shaving was a transactional business too with Gillete, until Dollar Shave Club came along and began a monthly razor subscription.

It is also important to note that some companies that are essentially transactional have elements of recurring in the sense that ways in which consumers engage with the product is much more predictable and reliable, thereby delivering the key benefits of a recurring model. Think Uber and Paypal, where they make revenue off of individual transactions, yet consumer purchases are very frequent and significantly more predictable. Or to a slightly lesser degree, Airbnb, where the average consumer would spend much more regularly and predictably (given the breadth of supply and use cases served) than with your average hotel chain.

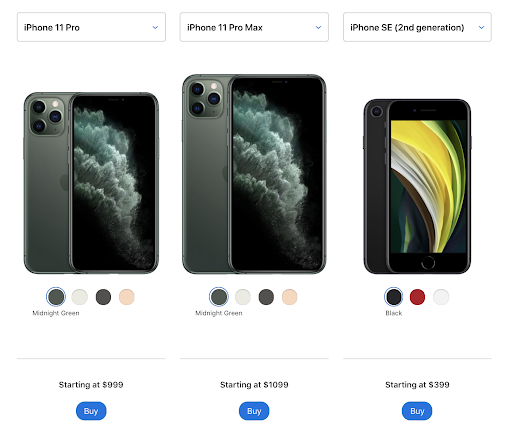

2) The “goldilocks principle”

Named after the famous fable where Goldilocks, faced with three bowls of porridge, found one to be too hot, one too cold, but the third just perfectly down the line, the goldilocks theory of marketing implies that it is best to offer customers three pricing packages to choose from (a high, low, and middle version). The reasoning being that:

- Customer psychology will naturally guide customers toward the middle priced option as that seems most balanced and “average” (so you want to make that an attractive one)

- It provides more flexibility to segment and land customers which will have different budgets and pricing expectations along

- It provides the context for future conversations around upsell by clearly outlining different product packages and tiered options

Apple has always been a great follower of the Goldilocks gospel –

Source: Apple

There are many levers to pull on to separate package versions, such as limits on users or data, different features, etc. Ideally you want your packages to be simple to understand and logically set up in terms of the tiering to align the upsell conversations with customers with their natural points of growth and product ROI.

3) The “endowment effect”

People tend to overvalue things that they already have, making it more often than not harder to to convert people from a competitor than to get them to buy something new. This is commonly called “switching costs”. Depending on how large the switching costs are, you may need to consider reorienting your pricing strategy when a prospect is using a competitive solution (giving the first month free, waiving implementation costs, etc). For example, mobile carriers will often pay out your existing device contract to switch from a competitive carrier.

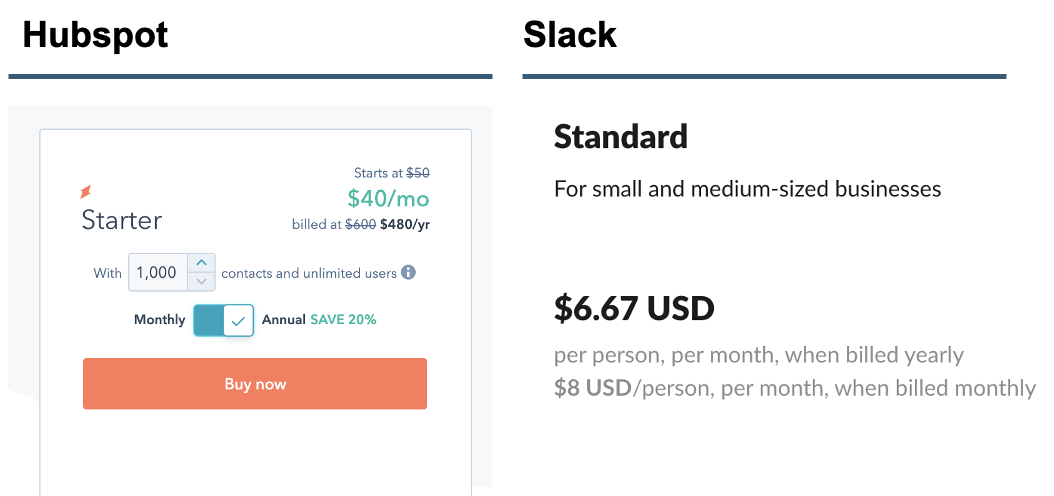

4) Encourage longer term upfront payments

When visiting the pricing pages of most leading SAAS companies, you will see a familiar toggle offering annual or monthly pricing, typically affording a discount in the range of 20-30% for paying annually.

Source: Hubspot (left) and Slack (right) pricing offering 20% and 16% discounts for annual

Source: Hubspot (left) and Slack (right) pricing offering 20% and 16% discounts for annual

The value of doing this is twofold. First – cash is king. It is such a simple rule, but the cheapest cash to any startup is cash from customers, much cheaper than cash from investors or debtors. Second – you will (most likely) see lower churn rates with a higher rate of yearly billing adoption (as customers, beyond being locked in, will have more time to adopt and implement your product).

When you get to a level of mature market dominance, you might even find yourself in a position to do away with monthly pricing options altogether, like Salesforce (only offers annual billing today).

Source: Salesforce

5) Consider longer term contracts

Even if it is not possible to charge your customers annually, and monthly is the only viable billing option, you may want to consider whether you can sign customers up for 1-year or longer contracts while billing them monthly. This won’t impact your cashflow but might impact your retention rates, give a stronger sense of forward looking projections, and give your success team more time to get customers to a point of comfort to reduce early activation failures. This is Salesforce’s standard approach – they will generally lock you in for 1 or 2 year contracts, while bill you monthly for the service.

Note, forcing customers into longer term contracts should never be viewed as a replacement for delivering on a great product/pricing promise to customers; it should purely be considered a strategy for enhancing your customer relationships.

6) Deliver pricing effectively

When engaging a customer in an inside or field sales conversation, always qualify before you quantify. The customer must earn their way to the price, do not offer it upfront. Push a customer to a demo first – you must use this to both understand the customer’s specific situation and challenges (listen) and position the value of your product in the best possible way in light of that (present). Get the customer to verbally agree on the value of the product in meeting their needs to then set the stage for a pricing conversation: “Based on everything we have discussed, would you like to move forward?”

Price always comes at the end. There will be times where the customer is pushy and you need to deliver a price. In this situation it is best to deliver a price range. For example: “well we offer some different package options and it depends on your needs – we have some smaller customers on the basic version at around $20K and some larger customers pay over $100k per year for our premium product.” Ranges are helpful so you don’t anchor the discussion too early. It is much better to deliver pricing over the phone than in writing.

Don’t jump to discounts; instead try to foster empathy. Don’t be afraid to admit being a young company and that you are still trying to learn from customers. Maybe ask what their concerns are with the price and how it could work for them.

7) Track pricing feedback

Use your CRM system or a simple google doc to collect important feedback on your customer conversations. Have a “loss” type field (to record why the customer declined the product – e.g. went with a competitor, pricing too high, wrong timing, went quiet, etc) and if the pricing was the factor then record the feedback on that. You may also want to track the customer journey in the sales process – what was their specific situation or point of interaction that was the catalyst for purchase.

8) When do free trial / freemium models work?

Saas companies used to solely offer “demos” or “free trials” to lure in leads, but the freemium model has become increasingly popular over the past decade. You see this model in services such as Dropbox, Tinder, LinkedIn, Spotify, Slack, Zoom, and The New York Times to name a few. Even in other verticals, the freemium model has prevailed – take gaming, where most of the popular games tonight like Fortnite are completely free to play and the monetization is strategically designed through in app purchases and upgrades.

Freemium models particularly make sense where a couple of factors exist:

First – there are strong network effects and virality benefits to your product, where people are likely to refer and share things virally with non-users (which you want to support) and/or the value of the product grows with the scale of users. If a product generates more value with more people using it—such as in viral products like Calendly or Zoom—freemium is a good way to go. Freemium products that grow with virality can also drive incredibly low CAC for users onto which you build an upsell or inbound sales model. You want to see users be evangelists of your product for freemium products to work.

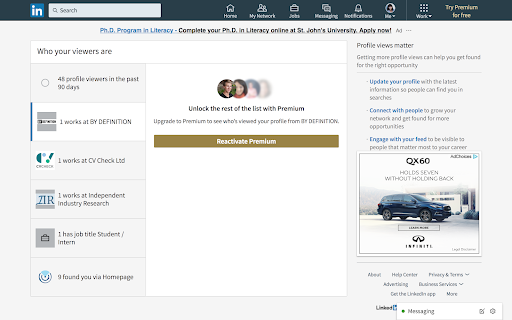

Second – your product is structured in a way that there are very logical in-product “stage gates” which create highly emotional impulses to upsell. A good example of this is Linkedin, who’s greatest pinch points are at the point where you want to send a message to a non-connection or do advanced searching.

Source: LinkedIn’s timely upsell prompts tied to “emotionally relevant” product points

For Slack, their most effective stage gates were around team features and the length of message archiving, a great way to segment out enterprises. For Zoom, their most effective stage gate is the 40 minute call limit which is a great way to segment out professionals. For Spotify, their stage gate is advertisements and the ability to create and store playlists.

Third, the feature differences between free and paid are simple to understand. Dropbox does a great job at this – free until 2GB of storage, then you must pay. LinkedIn, on the other hand, actually does a pretty poor job at this – the specific additional features that come with premium are somewhat unclear and the lines between packages are fairly blurred.

Fourth, the value of the features to the free user are compelling enough to encourage them to sign up, but not so valuable to cannibalize conversions to paid. A good example of getting this was the New York Times, who back in 2011 gave users 20 free articles a month. They soon realized they were giving too much away for free (and were seeing low conversion rates to paid), so cut this down to 5. On the other hand – it can be dangerous to cut back on features that are core to the product’s value from the free version as the user might not see any of the value and get frustrated.

Getting the balance right is critical. You want to track your conversions closely and test different strategies. If you are operating in a small market, you may want to shoot for a higher conversion rate (say 5-10%); if you are operating in a massive market, you might be comfortable with a lower (2-3% conversion rate).

Finally, your cost to successfully implement and serve the freemium users is low such that you are not significantly eating into your overall margins. Or, in the case of Spotify, you might actually find an alternative way to monetize the freemium to cover the costs – Spotify’s free version is supported through ad revenue. If your product requires personal handholding to successfully get customers set up and onboarded, freemium will be difficult.

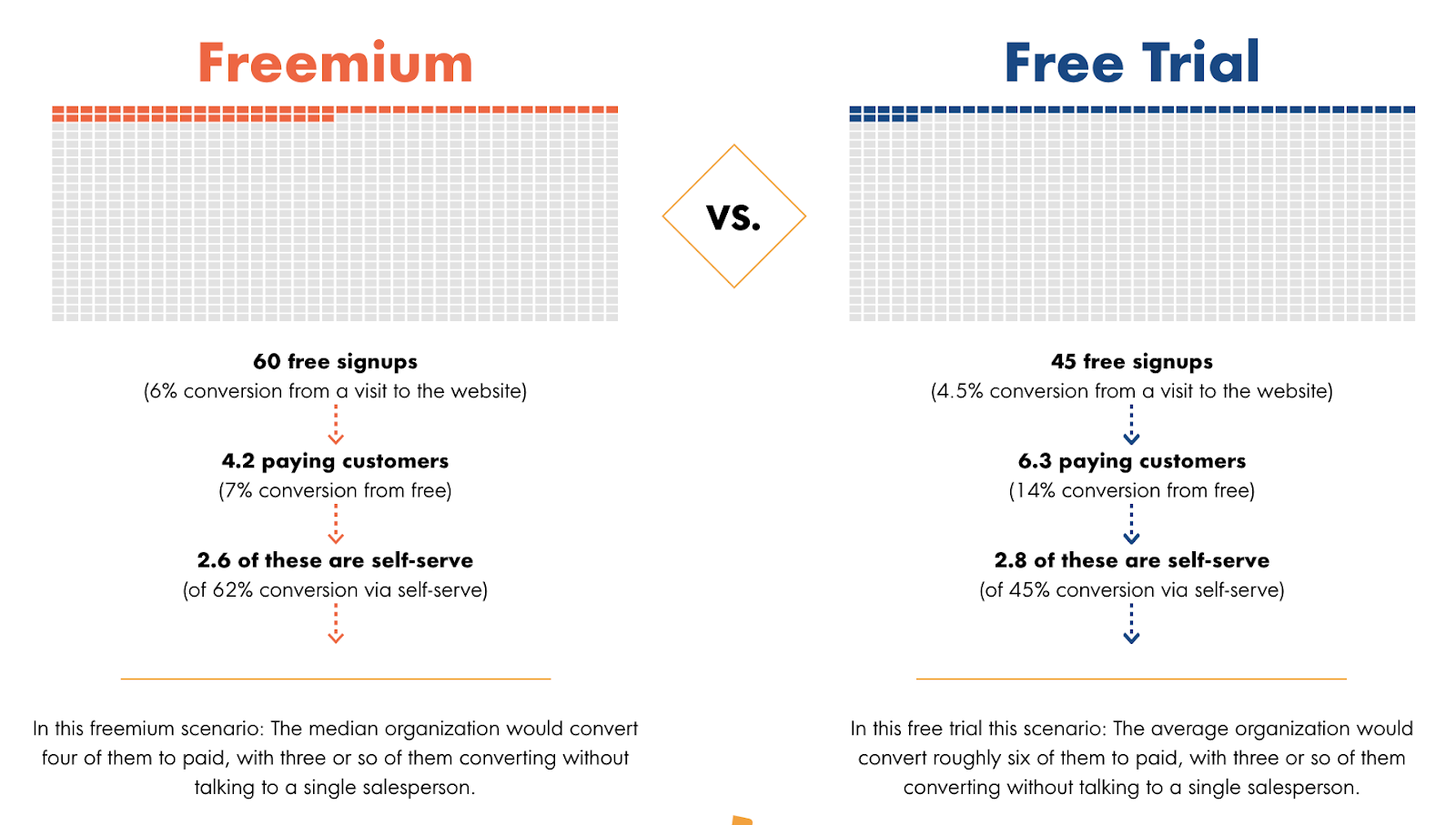

A recent Openview survey of 150 companies explored how free trials stacked up versus freemium models. They found that freemium generally opens up a business’s top-of-funnel much more, with typical freemium tools generating 33% more free accounts for every website visitor. However, unlike a never-ending freemium product experience, free trials drive urgency to purchase, made clear in the median conversion from free to paid being higher. If a business is laser-focused on maximizing conversion and near-term revenue, free trial might be a more logical option. That said, freemium products convert customers without sales 25% more often than a free trial model so tend to be more cost effective.

Source: Openview

Source: Openview

Case Studies

Atlassian – tying your pricing and sales model together

Atlassian entered the project management market with Jira in 2002. At the time there were incumbents who were defined by hybrid on prem and cloud solutions (Atlassian went all in on cloud only, which made their product development and management costs lower), fixed high price license options, and expensive field salesforces.

Atlassian, mostly by necessity (the team was bootstrapping and based out of Australia), dedicated to launch with no sales force and instead a very low cost (all options were under $5K as that was the max limit for most credit cards) and self-serve model with frictionless sign up. In turned out this model worked well, especially with the audience they were marketing too (devs) who seemed to respond better being sold to by a product and not a human.

Atlassian also switched the model from fixed licenses to user-based pricing. This allowed them to get broad market adoption with small teams into the funnel of their product and grow with them as they matured into enterprise. It turned out that in this space, broad product adoption was important to become the dominant “UI experience”. There are real “UI switching costs” in many markets – think how hard it is switching from IOS to Android or Mac to Windows – and this was one of them.

Finally, Atlassian in addition to the above, launched aggressive pricing campaigns in early days. They launched a 5-day campaign for Jira at $5 for all teams under 5 users, with all profits going to charity. In 5 days, they raised over $100k.

Source: Atlassian’s distribution flywheel

Slack – when freemium wins over free trial

Interestingly, Atlassian was on the other side of the table when it came to their team collaboration tool, Hipchat. Hipchat was first to the market and was growing very nicely. Atlassian set a simple pricing structure of $2/user and operated a free trial model followed by a forced credit card upgrade.

Slack on the other hand came into the market with a new freemium model — a completely free version of their product for all with a paid version set at $10/user. Even though their paid version was 5x the cost of Hipchat, this model won out at the end of the day. Why? Because –

- For every paid user, there were a lot of free users not using the competitive products (so it blocked out the competition)

- The product was very prone to virality, so those using the free version could easily refer others to join and adopt at a much higher rate and lower CAC

- It ensured that the Slack interface was the dominant experience in the market that users became accustomed too (creating “UI switching costs”) – Slack even made strong pushes into the college market to acquire users whilst they were students, so when they entered the work world they would take that love for product with them

- It gave an extended amount of time for Slack to invest in converting free users to paid (through direct sales or self serve product workflows), whilst Hipchat only had the short trial period to convert users after which they were lost.

Slack is also a great example of customer validation. Slack notoriously started out completely free for its early adopters (with no priced version at all). This allowed it to build a customer base and monitor usage to learn how users engaged with the product and where the key sources of value were. The team spent time talking to customers and reviewing usage data to ascertain the true sources of customer value. When they eventually “turned” on pricing for customers, they became a $1m revenue business overnight.

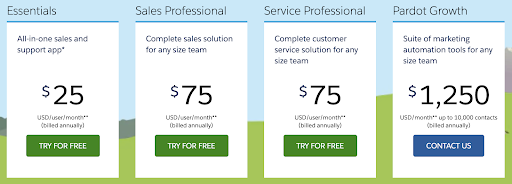

Salesforce – when a freemium version doesn’t make sense

Salesforce was one of the first, and is by far the most popular, cloud based enterprise-level CRM. When Salesforce was first conceived, nearly all software was on-prem, resulting in longer set-ups and less accessibility. Thus, when they launched in 2000, they had to also educate and convince users to try the cloud.

Salesforce initially launched with a freemium model where companies would be able have 5 free users, and as they grew from there, could add users at a relatively steep price of $50/user/month. This helped them to get smaller teams and startups into their funnel which would convert with their business scale.

However, overtime Salesforce has shifted away from freemium and their lowest pricing tier for startups under 10 people – their “Essentials” product – sells for $25/user/mo. This shift was likely driven by a couple of factors:

- Salesforce software doesn’t experience the same network effects across companies and between people, and thus, would not have benefited from the virality aspect that Slack did

- Implementing Salesforce is a “heavy lift” and often involves sales and customer success on the Salesforce side as well as customer resources for the data importing, configuration, feature customization, etc — this makes it harder to parse out features for a lite, self-serve version

- At this point, Salesforce has achieved market dominance (have 20% fo the CRM market) and no longer needs to price so aggressively for market share and awareness

Calendly – launching yourself into a market

Calendly runs on a freemium model that, much like Slack, leverages the simplicity of the platform to allow the tool to easily be distributed among a user’s connections. The platform went into beta testing with over 10k users, more than most launched products and which kickstarted their growth.

Once they launched and had users, they were easily able to add a paid premium version later that instantly converted some customers. The virality, ability to share, and ease of use of Calendy has made it a perfect candidate for the freemium model, as the core feature of the product being the sharing of calendars and meeting invitations at a high daily cadence with others made it a perfect candidate for virality and organic growth.

Individuals using Calendly can try out all of the features for 14 days, and then are reduced to the free version (with more feature restrictions) unless they choose to upgrade to a Premium ($8/user/month) or Pro ($12/user/month) version.

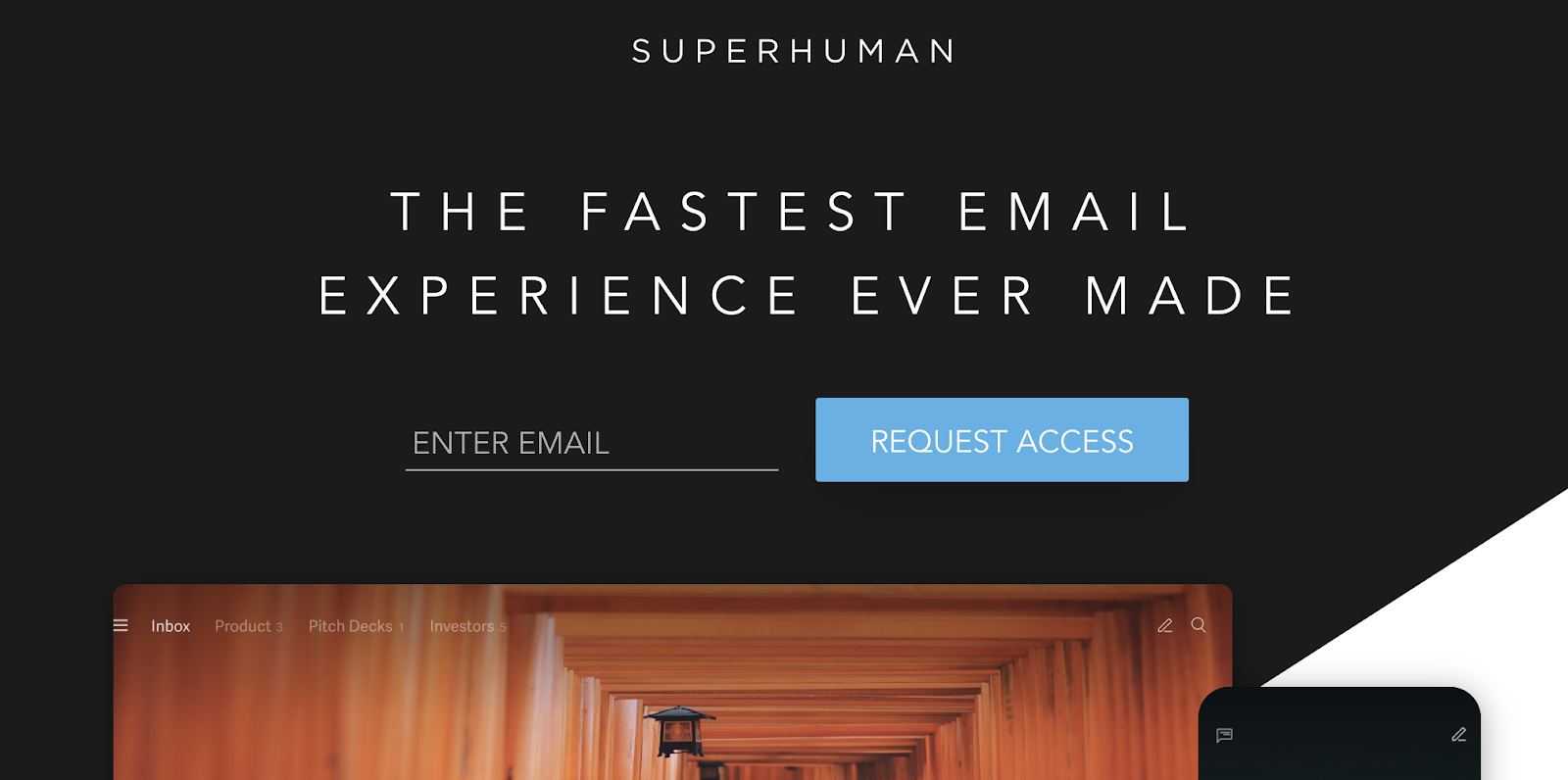

Superhuman – playing the luxury or exclusivity card

Superhuman is a fascinating case study as it runs in the face of many common theories of business – i.e. make your pricing transparent (Superhuman’s pricing, which is today approx. $30/mo, is completely opaque and unlisted), let your users self-serve where possible to keep sales costs low (Superhuman manually onboards every user with a personalized demo call), offer free trial or freemium options for lead gen (Superhuman offers neither, and you must “sign up” for the waitlist to be let in), don’t compete with free (Superhuman entered a market where they are taking on big incumbents such as Google and Microsoft who’s products (Gmail, Outlook) are completely free). Superhuman has charged at a competitive market and is choosing to compete on features and branding, not price.

If you visit Superhuman’s website today, you will not see any pricing or free trial options but rather a simple feature to enter your email to request access. In the early days, the only way to get access was to be “referred” into Superhuman by an existing user, with your acceptance more likely the more referrals you received. By stage gating access, Superhuman has created a sense of exclusivity and desire for entry much like the role of a bouncer outside the nightclub.

Source: Superhuman

Source: Superhuman

Superhuman is also fortunate to benefit hugely from organic and viral growth – all users’ emails are capped off with the tagline of “sent via superhuman”, and when the average person sends and receives 121 emails per day, that starts to add up. What is particularly smart with this strategy is that 1) their core target market of venture capitalists and startup leaders also happen to be an audience that is very likely to be in receipt of these emails (i.e. their target audience is dense in the organic referral audience); and 2) they have tied their branding to a highly attractive and aspirational goal – who doesn’t want to be “superhuman”?!

Good Reads

- Great perspective on sales tactics in field sales (First Round)

- Good review of general value based pricing theory (Sequoia)

- Good perspective on how to conduct buyer persona research (Hubspot)

- Review of when freemium works (HBR)